Francisco Perez (myztiko@gmail.com)

Introduction

Sunday, April 10, 1921 marked a milestone in Costa Rica's postal history. On that day, the Italian pilot Luis Venditti took off from San José at 11:45 a.m. for Managua aboard the Costa Rica, Ansaldo biplane, with a bag of mail officially marked and delivered by the Director General of the Post Office, a package of the Costa Rica Newspaper and three orders of jars of Blanco de Perlas Ideal. That sunny Sunday, the enterprising dream of a young pilot who, in love with life in our country, wanted to unite Costa Rica and Nicaragua by air, took off.

Although innovative, the idea was not entirely original. Civil aviation was barely eight years old when air mail transport had already been experimented in different parts of the world. The first official mail flight was made in India on February 18, 1911, when Henri Pequet, aboard a biplane, flew the first mail airplane in India. Sommer, In 1911, he transported some 6,500 letters and postcards from Allahabad to Naini, a distance of approximately 8 kilometers. That same year, on September 23, 1911, Earle Ovington, piloting a Bleriot, made the first postal flight in the United States, carrying a sack of 640 letters and 1,280 postcards between Garden City and Mineola (New York), a distance of just over three kilometers. On that occasion, Ovington did not land: he launched the sack from the air and, when it crashed, it tore, scattering the mail all over the countryside.

Ten years after those pioneering experiences, and barely eighteen years since the dawn of aeronautics, Luis Venditti was determined to put Costa Rica on the world map with a feat that required enthusiasm, institutional support and resources. In terms of official support, he had a fundamental ally: Gamaliel Noriega, General Director of the Post Office. According to Noriega himself, Venditti approached him in March 1921 to present his project of making an experimental flight to Nicaragua carrying a sack of mail. If the test was successful, he planned to offer the Central American governments a regular postal air transport service, a business with great potential at the time.

The context of international mail

It is worth remembering that in 1921 international mail was mainly transported by sea, which meant considerable delays. Mail between Costa Rica and Nicaragua, for example, was sent in ships that sailed along the Pacific coast and took between seven and nine days to travel the route between Puntarenas and Corinto. Therefore, any alternative that would drastically reduce these times was enthusiastically received. Venditti estimated completing the San José-Managua route in just two and a half hours, which was a remarkable technological leap for the time.

Private surcharge

In terms of resources, Venditti asked Gamaliel Noriega for authorization to issue -at his own risk- a private stamp of one colón. This issue would function as an additional surcharge that would pay for all the pieces transported in the experimental flight, the income from which would be the property of the aviator.

The design of the stamp was in charge of Antolín Chinchilla, who created a rectangular green vignette on an orange background. The motif included the inscription “First Air Mail - Costa Rica - Nicaragua, April 1921” and the facsimile signature of Luis Venditti, Italian aviator. The printing was done at the Litografia Minerva. Although the exact size of the print run is unknown, Noriega stated that some 600 stamps were sold at the Central Post Office in San Jose. Newspapers of the time -among them La Tribuna and Diario de Costa Rica- mention that the stamps were offered to the public at La Gran Vía The company's products have been well received and sold out quickly.

A relevant detail is that the vignette does not include the exact day of the flight. Far from being an oversight, this omission was due to the uncertainty about the definitive date: neither the aviator nor the authorities knew when the landing field in Nicaragua would be ready. On April 4, news arrived from the neighboring country informing that the field, covered with thirty rods of blanket to facilitate its visibility from the air, was ready. Therefore, the Costa Rica Newspaper on April 5 announced that the flight would take place six days later, i.e. on Sunday, April 10 at six o'clock in the morning.

Correspondence

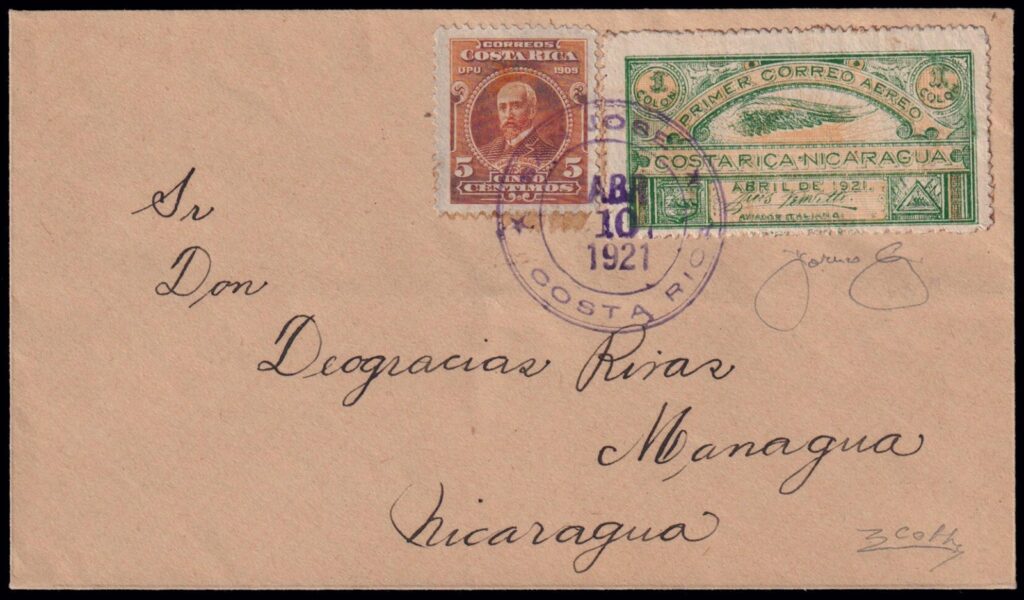

Mail destined for the flight had to pay both the ordinary international postage -five cents, according to the current rate- and Venditti's private surcharge. The official postage was effected by means of the 1910 five-cent issue (Scott 72). Thus, each postal piece had to bear two stamps: the official and the private.

This combination forced the General Post Office to establish an operational rule that would be key for later philatelic studies: the Central Post Office would only cancel the official stamp, leaving the envelope without postmark, since it was a private issue that could not receive the official stamp of the State. The postmark applied was the usual one of San José, dated April 10, 1921, and, according to Noriega's own testimony, he witnessed the cancellation of all the envelopes. Receipt of correspondence closed on Saturday, April 9, at 10:00 p.m.

Upon completion of the process, the correspondence - some 600 pieces - was placed in a new sack, adorned with the national flag and the inscription: “First Costa Rica - Nicaragua Air Mail. April 10, 1921.” The bag was delivered to Venditti at 5:45 a.m. on the day of the flight; however, takeoff was delayed until 11:45 a.m. due to mechanical failures.

The flight

Once in the air, Venditti said he was optimistic and determined to follow the route established by Fidel Tristán: west to the Pacific coast and then north, skirting the Gulf of Nicoya and the province of Guanacaste, bound for Managua. The estimated trip was a little more than two hours. However, adverse weather conditions forced him to divert. After flying over Chomes, the aviator zigzagged through Sarchí, Sarapiquí, Barra del Colorado, Matina and Limón and made a forced landing at the Santa Rosa farm at 2:15 pm.

Meanwhile, in San José, Noriega was following the development of the flight with concern. He had arranged for the telegraph offices to report the passage of the plane through their respective localities. San Antonio de Belen, Esparta and Chomes communicated their report, but no signal was received from the border stations. The Postmaster remained in uncertainty for about two hours until, after three o'clock in the afternoon, a telegram arrived from Limón notifying that the plane had crashed in that city.

Venditti later attributed the failure to the impatience of the public gathered in La Sabana, which pressured him to take off in hours of strong solar radiation, in unfavorable conditions due to rising winds and cloud formation. Curiously, he decided to fly without a compass, considering that it was only necessary for long flights; his plan -and his fuel- were calculated for two and a half hours.

In his account, the aviator acknowledged that, at the most critical moment of the trip, he had lost all orientation and that his only concern was to survive. He even thought he was approaching Corinto when, in reality, he was flying over Limón. He looked for a clear terrain to land and descended on a banana grove with tall grass, without noticing several fallen trunks: one of them hit the biplane's engine, which completely destroyed it.

The mailbag: its destination and contents

After the accident, Venditti was unharmed, although deeply affected by the loss of his aircraft and the failure of his project. He walked several meters along the railroad track that ran through the Santa Rosa farm, owned by the United Fruit Company. The administrator of the farm, upon learning who he was, attended to him attentively and arranged for his transfer to Limón on horseback, while four police officers remained guarding the plane.

Venditti returned to San José on the train from Limón, arriving on April 11 at 5:00 p.m. Journalists from The Tribune visited him that same afternoon and recorded a particularly revealing detail about the luggage he was carrying:

“While he was talking to us, we looked at the luggage that had accompanied him. Over there we saw a sack with correspondence, some boxes with labels of don Horacio Acosta, a package from the Diario de Costa Rica and many other things more.”

From this testimony it can be inferred that Venditti returned to the capital with the bag of correspondence in his custody and subsequently delivered it to Gamaliel Noriega, sometime after his arrival in San José, that is, after 6 pm on April 11.

Noriega, for his part, “opportunely” informed Nicaragua's General Communications Directorate of the failure of the flight and ordered the correspondence to be sent by sea aboard the steamship S.S. San Juan of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company. However, to date, there is no official record of the transfer of the bag from San José to Puntarenas, nor of its embarkation on the San Juan.

The contents of the bag

Noriega estimated that some 600 pieces of correspondence were dispatched. A note from the newspaper La Prensa (April 8, 1921) indicated that the bag contained two types of postal pieces:

- Official correspondence: a letter from President Julio Acosta García and each of his ministers to their Nicaraguan counterparts, as well as a letter from Noriega himself to his counterpart, Toribio Tijerino, welcoming the initiative of the first flight.

Since the presidential cabinet was composed of five ministers, it can be estimated that the total number of official pieces was seven. - Private correspondence: letters and packages from private citizens and companies, probably around 593 pieces.

Surviving correspondence from the flight

Costa Rican airmail specialists disagree on the exact number of authentic envelopes from this flight. Some claim that there are two known specimens; others mention three and some claim to have seen five. The author of this article considers that only two envelopes fully meet the criteria of postal and philatelic authenticity to be recognized as pieces transported in the Venditti flight bag.

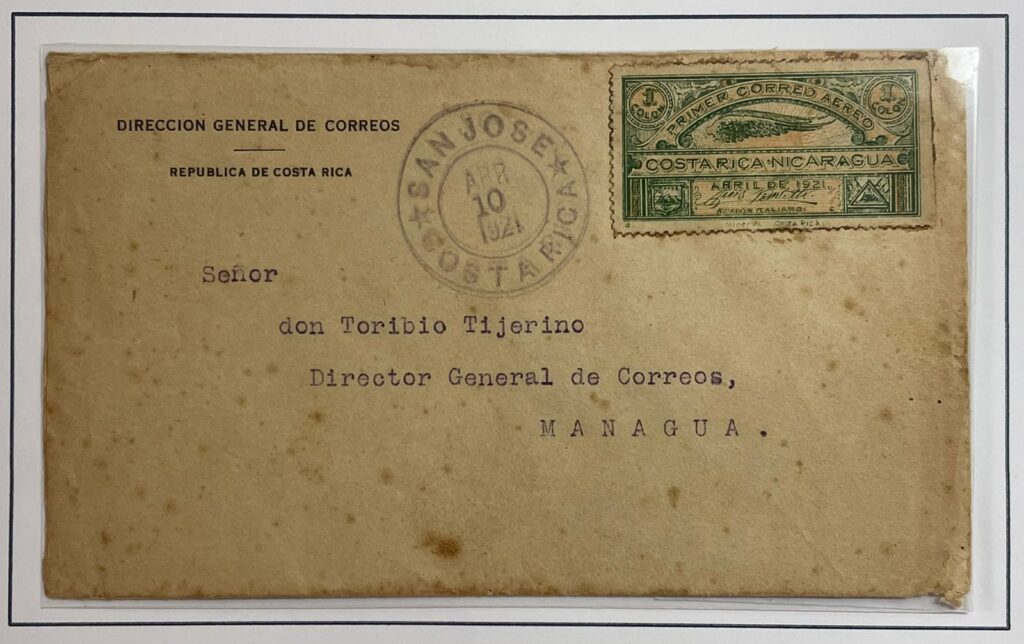

Envelope 1: Official correspondence from Gamaliel Noriega to Toribio Tijerino

Gamaliel Noriega reproduced in his 1934 article the image of this official envelope, addressed to his Nicaraguan counterpart. As it is official correspondence, it lacks ordinary postage, but bears the San Jose postmark and the green uncancelled surtax. The envelope has no transit or receipt marks on the back.

The absence of Nicaraguan postmarks suggests that it never reached its destination. It is plausible that, after the crash, Noriega retrieved the sack delivered by Venditti and removed the official letters, which contained messages celebrating a feat that did not materialize. Even so, this piece retains great historical value, as it actually traveled on the plane and is the only documented example of official correspondence from the flight.

Envelope 2: Correspondence from Antolín Chinchilla to Eduardo Echeverrí.

(Stanley R. Rice Collection)

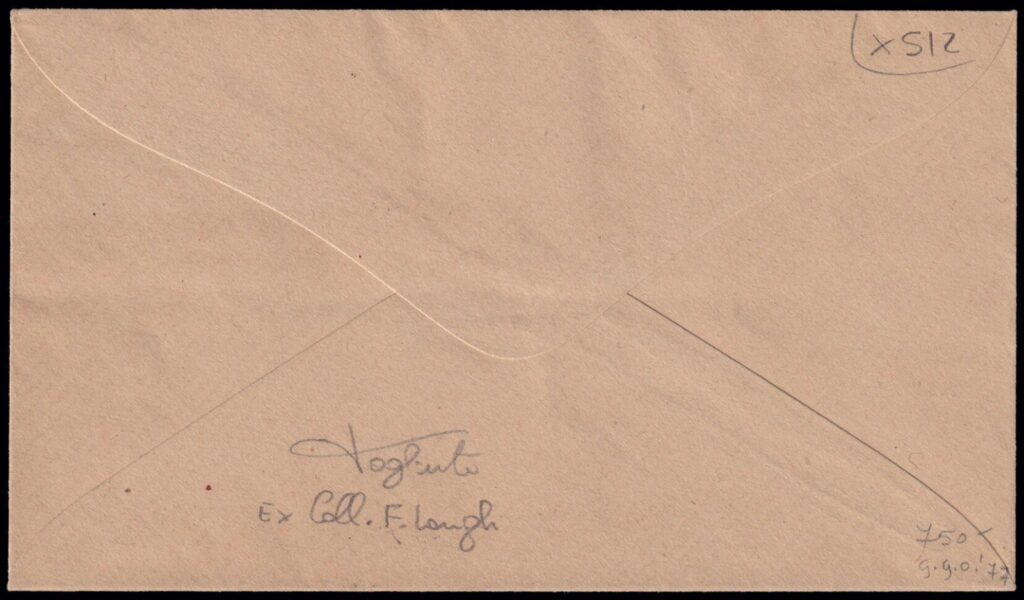

Stanley R. Rice published in Aero Philatelist Annals (July 1955) the analysis of this envelope sent by Antolín Chinchilla -author of the engraving on the envelope- to the Chief of Research in Managua, Eduardo Echeverrí. The envelope, franked with the 1910 5 centavos stamp (Scott 72) and cancelled in San Jose on April 10, 1921, also includes the green Venditti surtax, without Costa Rican cancellation, but postmarked upon arrival in Nicaragua.

The reverse shows the Corinto receipt cancel, dated April 19, 1921, which coincides with the estimated transit time of the steamer S.S. San Juan, which would have departed Puntarenas around April 12. The envelope also bears Diriamba and Managua markings dated May, indicating unsuccessful delivery attempts to the addressee. All Nicaraguan postmarks are of the duplex type, with a single circle and four parallel lines.

This specimen not only meets the requirements to be considered genuine, but also helps to reconstruct the logistical sequence between the return of the sack to San José and its eventual arrival in Nicaragua, supporting the hypothesis that the pouch was sent almost in its entirety by sea, contrary to the idea - held by some authors - that the mail was dismantled and the envelope removed from the envelopes.

Unfortunately, only poor quality black and white reproductions of this envelope are known and its current whereabouts are unknown.

Conclusion

Aviator Luis Venditti was a daring pioneer of Costa Rican aviation. Although fortune was not always with him, his initiative and courage contributed to the country an unforgettable chapter of innovation, risk and modernity.

From a philatelic perspective, the episode of April 10, 1921 is a milestone full of history, drama and mystery. The extreme rarity of the pieces of correspondence, duly transported on the flight, has given rise to apocryphal pieces and forgeries that continue to emerge at auctions, even with certificates of authenticity. Nevertheless, for scholars of postal history, the sack of mail that landed in Limón remains a source of fascination, scrutiny, as well as a tangible testimony to the pioneering spirit of Costa Rica at the time.

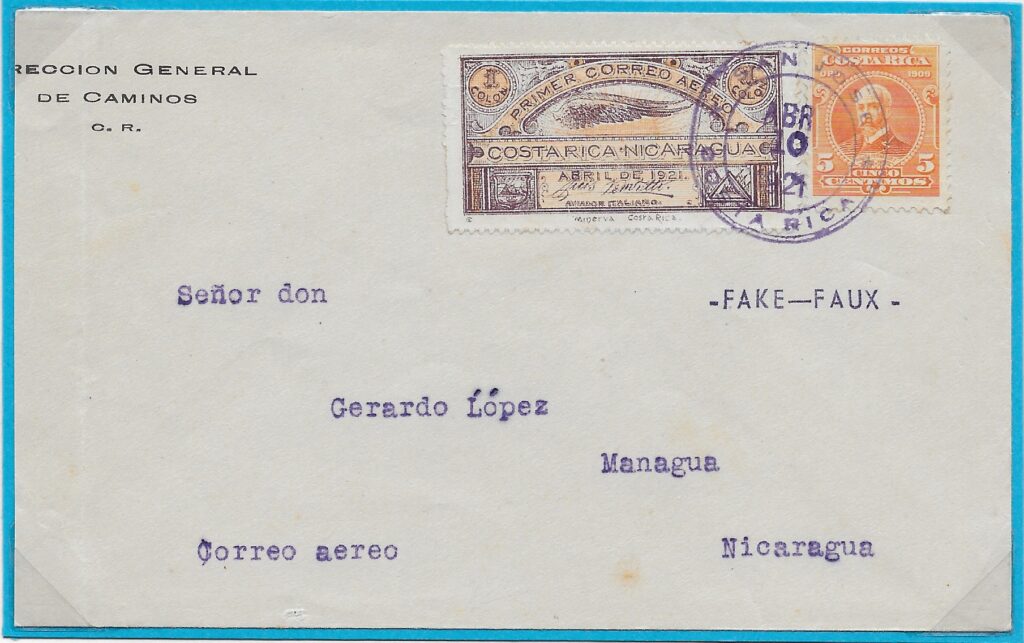

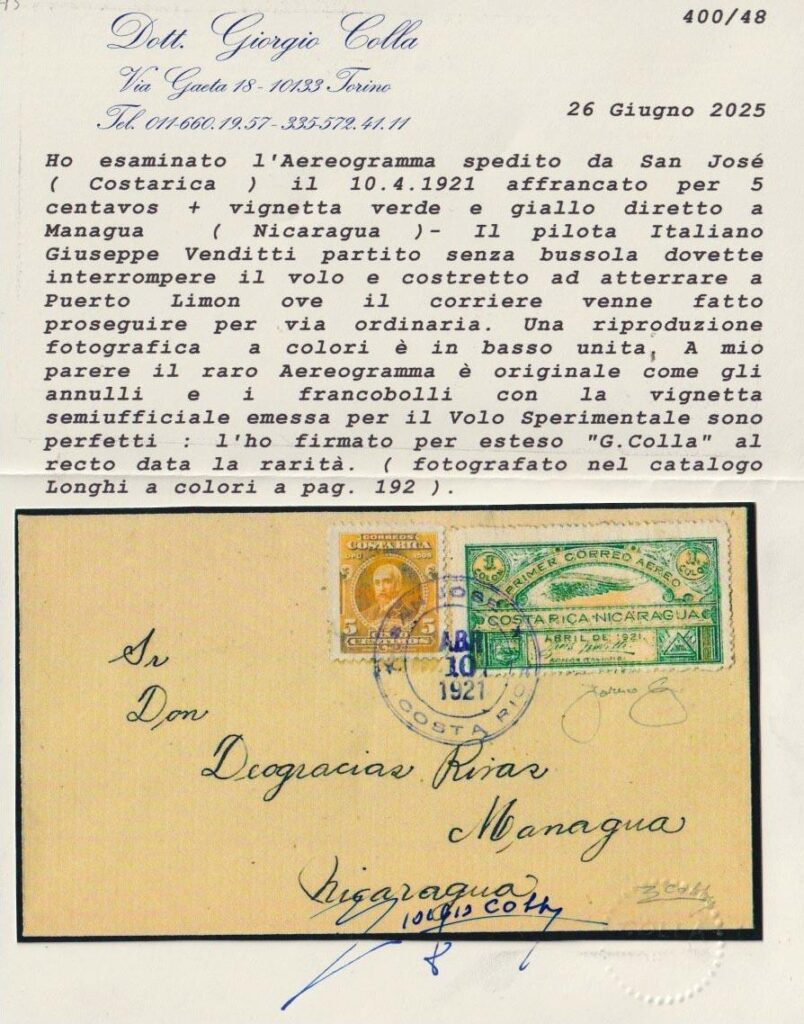

Fake parts:

This is another example of a fake envelope. This case is more delicate, since the envelope includes a certificate of authenticity.

Sources consulted

- Noriega, Gamaliel. First International Air Mail of Central America. Costa Rica Filatélica, Year II, No. 6, March 1934.

- Rice, Stanley R. 1921 Semi-Official Air Mails. Aero Philatelist Annals, July 1955. Reprinted in Airmail Postal History of Costa Rica, SOCORICO, 1999.

- 100 years ago, a letter envelope survived a plane crash in Costa Rica. Enrique Bialikamien (QePD). Revista Dominical, La Nación. April 17, 2021.

- The first inter-Central American air raid. Diario de Costa Rica, April 13, 1921.

- The gigantic flight of the Italian aviator Luis Venditti. La Tribuna newspaper, April 12, 1921.

- Venditti's flight, which will lead to Nicaragua. Diary La Prensa, April 8, 1921.

- Venditti's international flight. Diario de Costa Rica, April 5, 1921.

- How to send mail to Nicaragua by Venditti Airmail. La Tribuna Newspaper, Wednesday, March 30, 1921.